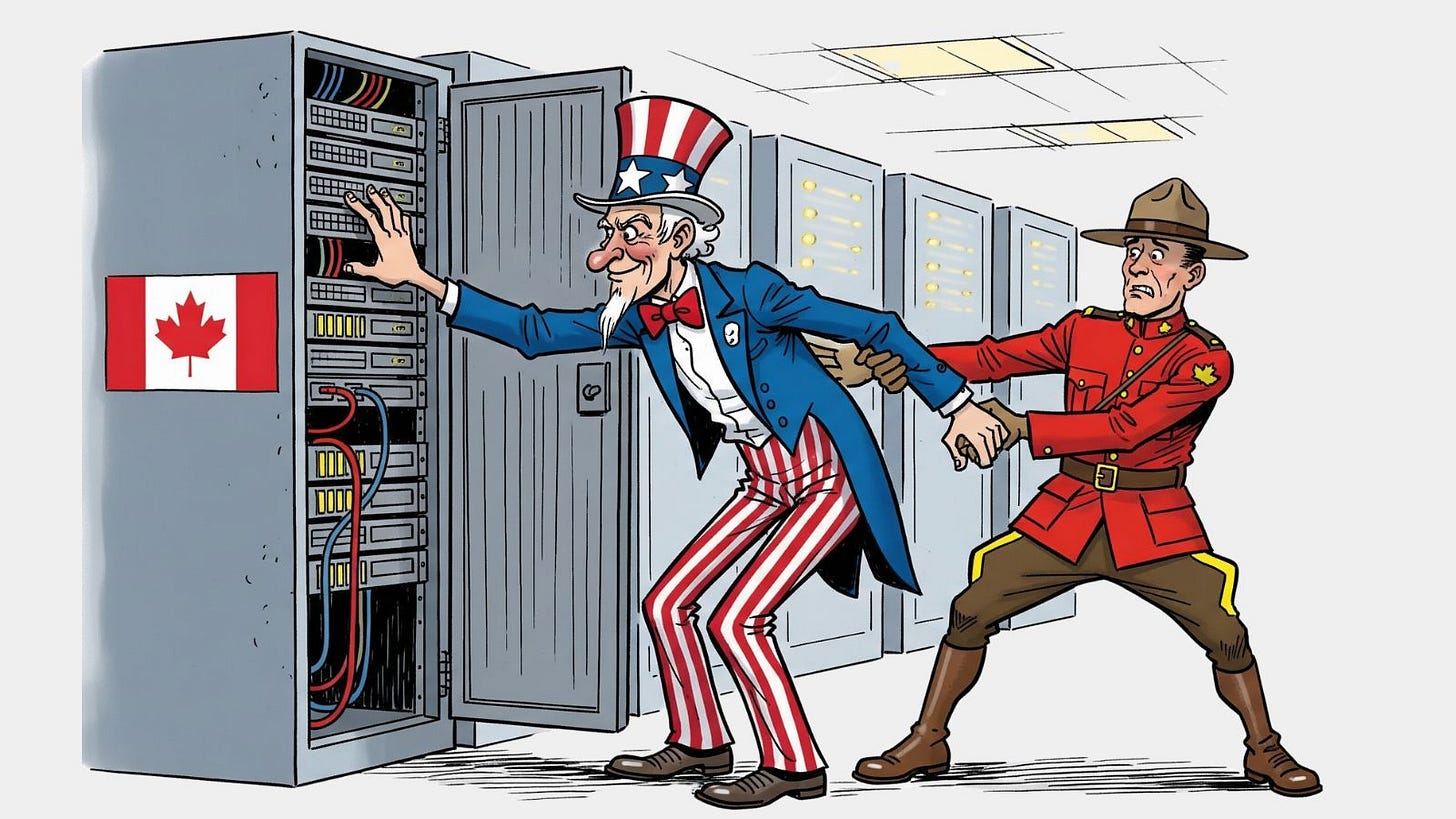

A Two-Part Series on Canada’s Data Sovereignty Debate

AI Generated Image (source)

This is a two-part piece on how Canada’s debate on data sovereignty has been misdirected towards the CLOUD Act. Part 1 focuses on the misdirection of the debate. Part 2 focuses on the impossible position U.S. cloud service providers find themselves in.

Part 1: The Real Threats to Canadian Data Sovereignty

Canada’s data sovereignty debate has been hijacked by the wrong Act. The Clarifying Overseas Use of Data or the CLOUD Act dominates headlines; but the real threat to Canadian privacy and sovereignty comes from laws most Canadians have never heard of: the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) and Executive Order 12333 (EO 12333). Until Canadians grasp this, any conversation about data sovereignty is misdirected.

Notwithstanding this reality, two important facts have emerged from Canada’s recent debate:

1. Canada’s reliance on U.S. hyperscalers subjects Canadian data to serious risks that must be assessed against a national sovereign data risk framework that Canada’s government has yet to develop

2. Total data sovereignty, or sovereignty by isolation, is an unattainable (and arguably counterproductive) objective in a hyperconnected world where innovation and growth are facilitated by openness

Frequently fused into these discussions are (often) fallacious references to the CLOUD Act (examples of such references can be found in content by CBC, Bell, Betakit, BNN Bloomberg and even my own Substack). The CLOUD Act essentially enables U.S. law enforcement authorities to access data held by U.S. providers around the world, under certain conditions.

Unfortunately, the more the CLOUD Act is referenced the cloudier (forgive me) things become. In a recent exception to the rule (but by no means the only one), Canadian law firm Osler published an informative piece on the Act that contributes to needed discussion on the serious risks to Canada’s data sovereignty. However, most CLOUD Act references mislead Canadians by disregarding the critical distinction between data access by U.S. law enforcement and data access by U.S. intelligence agencies.

Here is the issue: American attempts to access Canadian data for U.S. intelligence purposes represent a greater threat to the privacy rights of Canadians and Canada’s data sovereignty than attempts to do so for U.S. law enforcement purposes, especially since access under the CLOUD Act by U.S. law enforcement includes additional safeguards for individual privacy rights, including a legal basis upon which a company could challenge court orders under the Act.

To inject some needed clarity in the national data sovereignty discussion, Canadians consequently need to distinguish between access by U.S. law enforcement and U.S. intelligent agencies when evaluating data sovereignty risks.

FISA & EO 12333: What Really Matters

While the Canadian government quietly acknowledged FISA as a “primary risk to data sovereignty” in a 2020 white paper, references to EO 12333 by the government or in Canada’s public debate on data sovereignty are far more scarce (nearly non-existent). In the post 9/11 era, American surveillance practices, described as “collect it all”, have significantly relied on both FISA and EO 12333. They make the CLOUD Act seem quaint.

FISA: Foreign Data Is Fair Game

If the CLOUD Act is a distraction, FISA is the main event. FISA entered into force in 1978 and has been amended multiple times (particularly post 9/11). It grants U.S. intelligence agencies the authority to order cloud providers to provide them with access to sensitive customer data for the purpose of acquiring foreign intelligence.

Section 702 of the Act, which has been reauthorized multiple times since its introduction (and is again being debated in the U.S.) currently empowers U.S. intelligence agencies to access the data of non-U.S. persons outside of the U.S. without a warrant. Outside of Section 702, FISA does contain limited safeguards by requiring intelligence agencies to demonstrate probable cause and obtain a warrant from a secret FISA court prior to engaging in foreign surveillance.

Here is another catch: FISA requires cloud providers to comply with FISA orders without notifying their customers in order to ensure “the secrecy of the acquisition.” No one therefore really knows how many instances FISA has been used to access data outside the U.S., allowing for claims, such as those made by Osler, that “there are no documented cases [emphasis added] of foreign government…access to the data of Canadian enterprises processed within cloud services”.

However, legal and data security teams across the globe should be concerned that a significant portion of intelligence Washington relies on is obtained through Section 702 (bypassing the need for a warrant, a judge’s involvement or customer notification). The Office of the U.S. Director of National Intelligence (DNI) advertises Section 702 as an “invaluable source of intelligence on foreigners located outside the U.S.” and interestingly notes that in 2022 “59% of President’s Daily Brief Articles contained Section 702 information reported by the National Security Agency.”

EO 12333: A Shadow Authority

FISA, however, is only half the story. The other half operates with even fewer constraints: EO 12333. This order came into effect in 1981 and provides U.S. military and intelligence agencies with expansive powers to conduct global surveillance without being limited by FISA safeguards such as court authorizations or probable cause requirements. Its principal application is against “foreign persons…outside the United States” as it aims to fill gaps in intelligence collection authorities that are “not otherwise regulated by FISA.” What very little we do know about specific instances where EO 12333 has been leveraged by the U.S. reinforces the notion of America’s “collect it all” approach to surveillance.

The sole source of public information on operational details of U.S. surveillance practices under EO 12333 has been the (in)famous 2013 Edward Snowden leaks. Four NSA/CIA programs that collected data under the authority of FISA or EO 12333 illustrate the challenges to Canadian data sovereignty presented by the American approach to foreign surveillance.

1. CO-TRAVELER: Monitors the movement of individuals by collecting billions of cellphone locations every day and tracks individuals “into confidential business meetings or personal visits to medical facilities, hotel rooms, private homes and other traditionally protected spaces.”

2. Dishfire: A bulk collection program that collects the content of nearly 200 million messages from phones globally.

3. SOMALGET: A global national wiretap initiative that records phone calls made in different countries.

4. PRISM: A collection program approved by the secret FISA court where the NSA purportedly extracted “audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs” from the central servers of nine leading U.S. internet companies. After PRISM details, including internal Top Secret NSA slide decks, were publicly leaked, most companies denied any knowledge of the program or providing the NSA direct server access, while emphasizing customer data is only disclosed in response to lawful orders (which FISA requests fall under). Data collected under PRISM reportedly constituted the single largest source of intelligence in the President’s Daily Brief.

Nominal Oversight

EO 12333: The NSA claims that “every type of collection undergoes a strict oversight and compliance process internal to NSA.” Aside from this declaration of intent to self-police by the NSA, there are effectively no rules or safeguards that subject the collection practices under EO12333 to any form of oversight. Bi-partisan Congressional requests for further information have highlighted concerns that collection practices under EO12333 have occurred “entirely outside the statutory framework that Congress and the public believe govern this collection.”

FISA: The Office of the DNI avers that the Government’s use of Section 702 “is subject to a robust compliance regime” involving the secret FISA court and all three branches of government. Bi-partisan Congressional majorities have repeatedly reauthorized FISA since inception. Unfortunately, these limited internal and secretive oversight mechanisms, in conjunction with FISA’s secrecy requirements, provide foreign nations and the public with nearly no insights into how effective these safeguards are in practice.

Tenuous Transparency

Prior to 2014, U.S. technology providers were not permitted to report any information regarding U.S. national security demands. Following the 2013 Snowden leaks and litigation by Microsoft (and other technology providers) against the U.S. government in 2014, the U.S. allowed these companies to publish some data on FISA orders.

Today, both Microsoft and AWS issue bi-annual information request reports which disclose the number of requests received (not acted on) within a given range (specifics and details remain prohibited by law). This reporting structure obscures how often access under FISA is provided to the U.S. government, thereby complicating efforts by Canada to evaluate the risk FISA requests pose to Canadian data sovereignty. Further complicating these efforts is the fact that no information about EO 12333 is included in the transparency reports of U.S. providers. This is highly unlikely to change. And that is the real danger for Canada. It isn’t that Washington can access Canadian data; it’s that it doesn’t need to ask and rarely needs to tell.

Why This Matters For Canada

In short, the scope and scale of these collection practices means that Canadian data may already be swept up in U.S. surveillance nets, whether or not anyone knows it. These leaks are almost certainly just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, especially for collection under EO 12333, and Canadian policymakers should know it.

Furthermore, the American legal system only safeguards American data, leaving everyone else exposed. The U.S. public debate on the privacy implications of such programs have also always centered around U.S. persons, never foreigners or allies.

Since the U.S. government has not provided any information on these programs after their existence was revealed by Snowden in 2013, we do not know whether they have ceased, scaled up or down over the past decade. These American surveillance laws would matter less if Canadian data weren’t sitting on U.S. servers. However, that’s exactly where Canada has stored it.

A separate risk category exists for Canadian companies who have U.S. domiciled subsidiaries because this places those companies directly in the crosshair of U.S. law, allowing Washington to bypass cloud service providers when initiating demands for their data. Major Canadian banks like RBC, TD, BMO, CIBC and Scotiabank fall into this category.

For Canada, the implications are immediate: as long as Canadian ministries and enterprises host sensitive data on U.S. platforms, or set up shop in the U.S., American surveillance regimes effectively extend into Canadian networks.

Part 2: Between a Rock and a Hard Place: U.S. Providers & The Sovereignty Dilemma

Any successful business strives to satisfy their customer. Recently, and in response to growing global geopolitical frictions, this has resulted in Microsoft, AWS and other U.S. providers each offering some version of a “sovereign cloud” that putatively provides customers with complete control over their data.

Unfortunately, the tension created by seeking to simultaneously reconcile the increasingly contradictory objectives of U.S. national security with shareholder interests and customer requirements places U.S. cloud service providers in the difficult position of offering commitments regarding the protection of customer data that may be impossible to meet in practice.

Take, for example, the recent set of motions approved by the Dutch parliament that call on the government to end dependence on U.S. cloud providers and reexamine the government’s decision to select AWS as Holland’s internet domain hosting partner. Amazon responded with a statement that their sovereign cloud ensures customers have “full control over where they locate their data, how it is encrypted and who can access it.”

AWS’s assurances sound comforting but reality, captured in fine print, is murkier. Yes, customers may have full control over their data, but it is unclear whether they have exclusive control. So long AWS or any other U.S. provider is subject to FISA or EO 12333 requirements, they may be unable to provide customers with exclusive control over who can access their data.

Promises Vs Reality

U.S. providers, Microsoft in particular, have gone great lengths to reassure customers that they would never voluntarily disclose any customer data to the U.S. government. Arguably, these global companies have a greater interest in prioritizing customer satisfaction over U.S. national security objectives.

Microsoft publicly “disagrees with these laws [FISA]” and argues that secrecy should be the exception not the rule. Notably, Microsoft has also raised concerns about gag orders and “recently challenged the U.S. government in court again, arguing that the Justice Department routinely uses overly broad and indefinite gag orders that prevent us from ever notifying customers of requests for their data.” It is also worth noting that Microsoft’s Data Law FAQ page directly addresses misconceptions about the company’s involvement in PRISM. Given Microsoft’s commercial interests and track record of advocacy against U.S. surveillance overreach (both in U.S. courts and Congress), its criticisms of these laws seems genuine.

Since Microsoft is more transparent with details about its advocacy regarding FISA and EO 12333, it is difficult to conduct a direct comparison between the attitudes and approaches of AWS and Microsoft towards U.S. national security objectives. However, several notable commonalities exist.

Amazon Web Services: In the AWS Data Processing Addendum, which supplements the AWS Customer Agreement and applies globally, AWS states that it does not access or use customer data except as necessary to comply with the law or a binding order of a governmental body. Upon receiving a legal request, “AWS will use every reasonable effort to redirect the Requesting Party to request Customer Data directly from Customer.”

If AWS is compelled to disclose customer data, it commits to promptly notifying the customer “if AWS is legally permitted to do so.” “If AWS is prohibited from notifying Customer about the Request, AWS will use all reasonable and lawful efforts to obtain a waiver of prohibition, to allow AWS to communicate as much information to Customer as soon as possible.”

Importantly, AWS states that “we prohibit - and our systems are designed to prevent - remote access by AWS personnel to customer data for any purpose, including service maintenance, unless that access … is required to comply with law.”

Further, AWS “challenges law enforcement requests that are overbroad” or where it has “any appropriate grounds to do so.”

Microsoft: Similarly, Microsoft only commits to disclosing data for legal compliance reasons and it’s Data Law page states that “we always attempt to redirect the government to obtain the information directly from our customer…just as they did before the customer moved to the cloud.” Microsoft also gives prior notice to its enterprise customers of any third-party requests for their data, “except where prohibited by law.” “In some cases”, Microsoft challenges gag orders but the secrecy of the FISA court makes it nearly impossible to know whether any company has challenged such orders. Unlike AWS, Microsoft does not explicitly acknowledge that Microsoft personnel retain the ability to remotely access customer systems when required law. This, however, is strongly implied. Ultimately, even the best-intentioned corporate promises collide with the hard edge of U.S. law.

The Compliance Paradox: When Laws Beat Encryption

If complying with FISA or EO 12333 orders requires remote access to systems by AWS or Microsoft employees, how effective are services like AWS’s External Key Store encryption system as guarantors of data sovereignty? If U.S. parent companies do not retain remote access to Canadian customer data, how can they comply with legal orders under FISA or EO 12333? Will compliance via remote access circumvent the leadership of a U.S. provider’s Canadian subsidiary or will the Canadian subsidiary have an opportunity to refuse a request? What are the consequences for noncompliance in such cases?

Since each U.S. provider offers customers different forms of data encryption, what will the U.S. government response be if a U.S. provider rejects a request on the basis that it has no control over data that is controlled by a Canadian subsidiary subject to Canadian laws? And what is the point of a Canadian subsidiary if a U.S. parent company can circumvent its leadership via remote access by U.S. personnel?

Furthermore, what are the legal grounds to challenge orders under FISA or EO 12333 (including gag orders) if U.S. national security is deemed to be at stake? How likely is it such a challenge would succeed? Will any sovereign cloud pledge or initiative by U.S. providers change the reality that U.S. government surveillance laws demand uncompromising compliance?

These are questions that Canadian policymakers and organizations need to grapple with for a comprehensive assessment of risks to Canadian data sovereignty.

Europeans recognized their lack of leverage after being forced to submit to FISA and EO 12333 requirements despite the clear conflict this created with the GDPR and Data Privacy Framework (which regulates data transfers between EU and U.S.).

Since U.S. providers have little to no control over the U.S. government’s national security objectives and surveillance laws, they are placed in the difficult position of complying with legally binding orders that undermine the trust that is essential to successful business relationships with their customers who they have every incentive to please (especially in large markets like the EU).

Comply Or Else: The Case of Yahoo

In 2007-2008 Yahoo legally challenged an expansion to U.S. surveillance laws. Yahoo refused to comply with what it viewed as “unconstitutional and overbroad surveillance.” Ultimately, the challenge failed and the secret FISA court demanded that the user data in question be turned over to the government. However, Yahoo did succeed in declassifying parts of the case in order to share the findings with the public. Such a declassification of FISA court proceedings is “extremely rare.”

At one point, the U.S. government went as far as to threaten Yahoo with daily fines if it refused to comply. How many and what kind of threats has the U.S. government made against U.S. providers that remain unknown? How aggressively will different U.S. administrations pursue data access requests in a time of great-power competition? Canada’s data sovereignty rests heavily upon answers to these questions. These sovereignty risks are not a matter of trust in U.S. companies but a function of U.S. law.

Future Policy Paths for Canada

As Cold War 2.0 intensifies, we can expect growing geopolitical tensions to produce spillover effects that impact decisions around data sovereignty. For nations, trust in the cloud will become more of a geopolitical wager, not a technical guarantee. U.S. providers will continue to market sovereign clouds as solutions, but American laws, not domestic servers, will determine who controls Canadian data.

Europe will continue to serve as a case study worth observing. Earlier this year, Microsoft notably offered its most extensive combination (to date) of technical and legal measures designed to reassure its European customers about the security and resilience of Microsoft services. Nevertheless, only a few months later, two major Danish municipalities made global headlines for a decision to quit using all Microsoft services amidst sovereignty concerns. It is unclear what other options are left in the toolbox to help build trust between U.S. providers and their non-American customers so long as FISA and EO 12333 remain law.

Both Europeans and Canadians confront the same reality: their sovereign ambitions outpace their domestic cloud capacity. One nascent and interesting development in Canada worth further analysis has seen four Canadian cloud providers (ThinkOn, Hypertec Group, Aptum and eStruxture) combine forces to offer the Canadian government Canada’s “first end-to-end, sovereign and AI ready government cloud”, with each company contributing a different element (e.g., data center facilities, hardware, cloud and data services). Of these four, only ThinkOn is currently eligible to sell cloud services to the government.

Another avenue for Canadian policymakers to explore is how to cultivate public-private partnerships with E.U. governments and U.S. cloud service providers to pushback against the expansive “collect it all” approach to U.S. surveillance practices as the U.S. Congress debates reauthorizing FISA. What Canada should not do is backtrack on critical partnerships with hyperscale cloud providers that constitute a critical part of Canada’s social and economic fabric and national modernization efforts, particularly those of Canada’s Armed Forces.

Finally, as a first step to mitigate the serious risks to Canada’s data sovereignty, the government should lead a national effort to develop a Canadian sovereign data risk framework that can be used by public and private sector organizations for a common baseline assessment of risks to Canadian data. A helpful starting point may be the Digital Governance Council’s Framework for Geo-residency and Sovereignty, a standard that “specifies the minimum requirements for organizations to protect data assets that reside in foreign entities.” Ultimately, sovereignty in the cloud is not a product, it is a policy choice. So, will Canada continue to rely on U.S. goodwill, or will it work towards the sovereign data framework it needs?